Maps

PEI Map (1832)

PEI Map (1832)

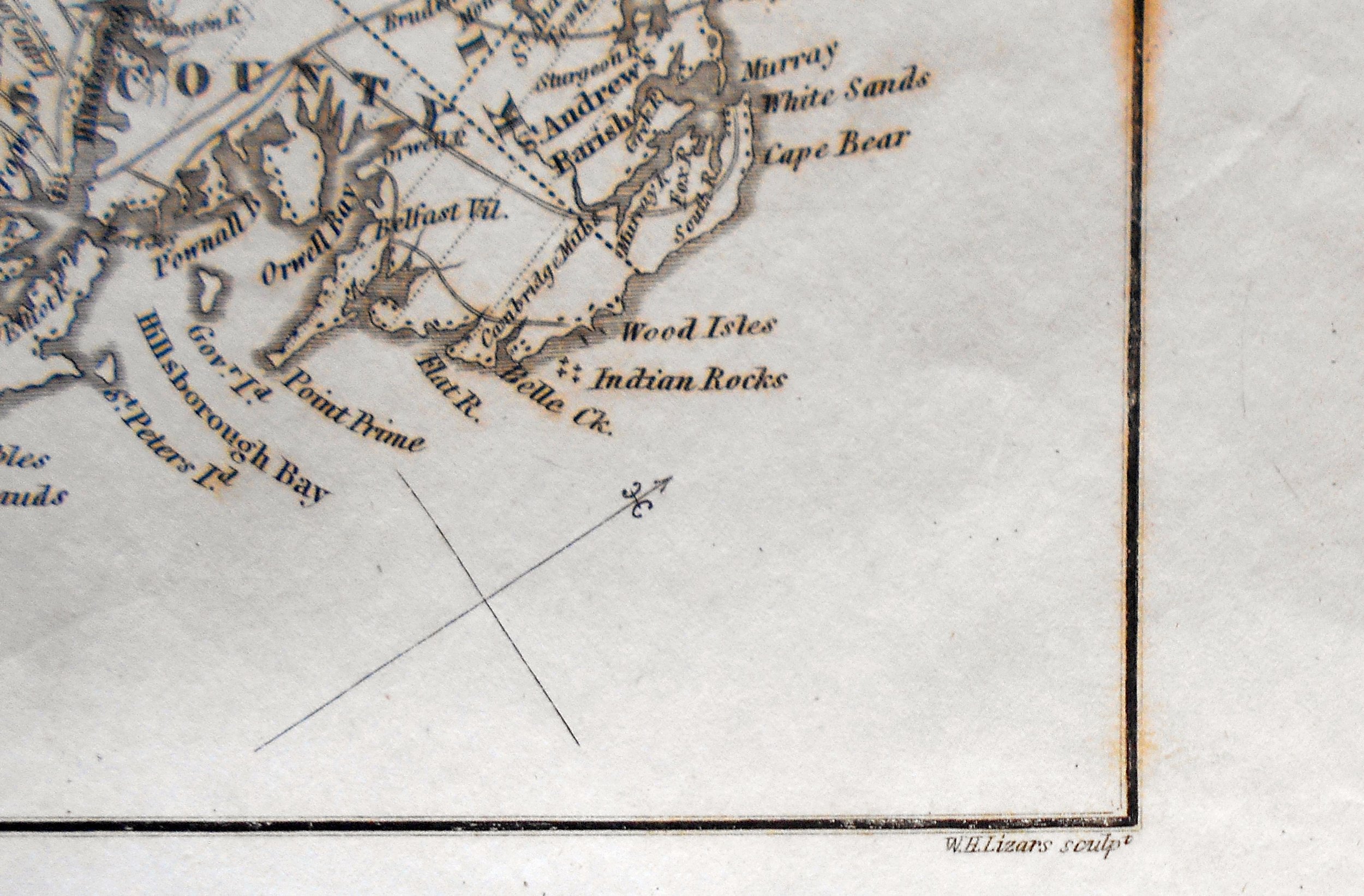

Title: Map of Prince Edward Island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence for McGregor’s British America

Engraver: W.H. Lizars

Description: Liberated from a printing of British America by John McGregor. The book was published by William Blackwood, Edinburgh, & T. Cadell, London, 1832. Map image measures 4 1/4 x 6 3/4” (10.8 x 17.1 cm) to the neat line. Shows foxing and age toning.

John MacGregor (1797-1857) was a merchant, landowner, civil servant, politician, and writer. He was born at Drynie, near Stornoway, Scotland, and died in Boulogne, France.

Young MacGregor immigrated with his parents to Pictou, N.S., in 1803. Three years later, the family moved to Covehead on Prince Edward Island and took up 50 acres on Sir James Montgomery’s Lot 34. In 1819, MacGregor advertised in the Prince Edward Island Gazette that he intended “to commence Business in this Town [Charlottetown]” with stock from Halifax, largely gin, rum, and dry goods, “sold cheap for cash.” As well as running this mercantile establishment he obtained several lots in Charlottetown from Montgomery’s agent James Curtis, served as Curtis’s attorney, and in 1823 succeeded him as agent for the Montgomery interests on the Island. On 7 May 1822 MacGregor had been appointed high sheriff of the Island, an onerous office held for a year as a civic duty by aspiring young politicians. By June of 1826 MacGregor was publicly advertising that he was leaving the Island and that his business would be taken over by two of his brothers. He moved to Liverpool, England, in 1827 and set up as a merchant and general commission-agent; of this endeavour the London Times later wrote: “His mercantile speculations were there unfortunate, and, indeed, rarely at any period of life successful.” So unfortunate were they that he ultimately offered his creditors seven and a half pence on the pound as an alternative to bankruptcy. Having travelled extensively in British North America and between the colonies and Britain, often aboard the newly inaugurated steamships, and having talked at length with businessmen about commercial prospects and emigration, MacGregor decided to become a political economist and commercial expert, at first specializing in Britain’s American colonies. He became acquainted with James Deacon Hume and other political economists and began a lengthy writing career which resulted in the publication of more than 30 titles, many of them multi-volume works. His output included several travel accounts, a number of compilations of commercial data, and an incomplete history of the British Empire which, in its first two volumes, managed to get to 1655. Contemporaries were most unkind to MacGregor’s writing, one commenting, “We do not imagine that any one except the printers ever read these works through; yet the true historical writer might find in them useful materials for his purpose.” Although this assessment may apply to many of his later publications, his first works, published between 1828 and 1832, were and are worth reading from beginning to end. In them he was able to rely on his own observation and experience and, emphasizing publicity for the various provinces of British America to a British audience, showed at his most attractive. Particularly interested in bringing the advantages of the “Lower Provinces” to the attention of the British, MacGregor concentrated upon the Atlantic region in these early writings. In Historical and descriptive sketches of the Maritime colonies of British America (1828) he devoted an inordinate amount of space to Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland, commending the former for its ideal climate and recommending a legislative government for the latter. In Observations on emigration to British America (1829) he asserted: “The retention of our North American Colonies is an object of such importance, that the very idea of abandoning them cannot be for a moment defended on just or political principles.” The colonies needed immigrants, but “to gentlemen educated for the professions of law, divinity, or physic, British America offers no flattering prospects.” Farmers, artisans, and labourers, industrious and healthy, were what British North America required. In British America (1832) he insisted that most errors and blunders in colonial policy were a product of “the meagre information possessed by our government” rather than neglect, and he maintained that British North America was more valuable than ever in the age of steam because it possessed coal in such abundance. He prophesied that British America, including the land west of the Great Lakes, was “capable of supporting” a population of 50 million, and that those who held this territory would have the power for “the umpirage of the Western World.” If Britain lost her North American colonies they would probably merge with the United States or at least form an alliance with the northern states which would tarnish Britain’s magnificence and diminish her political consequence.

Source: J.M. Bumstead, Dictionary of Canadian Biography

William Home Lizars (1788–1859) was a Scottish painter and engraver. In 1812, on the death of his father, Lizars carried on the business of engraving and copperplate printing in order to support his mother and family. Lizars perfected a method of etching which performed the functions of wood-engraving, for illustration of books.